|

|||||||||

Suicide Among Youth Depression is closely linked to suicide. Symptoms of depression include feelings of sadness and hopelessness, apathy, sleep problems, decreased energy, changes in appetite, inability to concentrate, feelings of worthlessness and thoughts of death or suicide. Depression in children is diagnosed by observation of persistent changes in mood—either depressed or irritable mood and/or loss of interest—plus four or more of the following symptoms present for 2 weeks:1

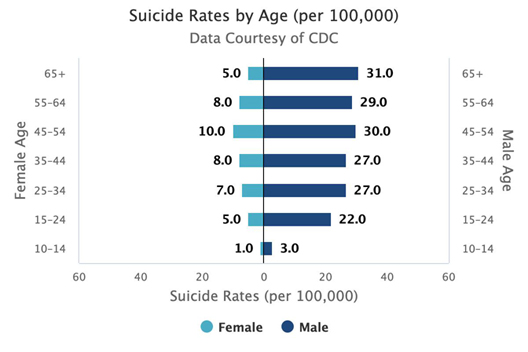

Depression is a common illness. About 2% of children and 4% to 8% of adolescents are affected by major depressive disorder. Depression in childhood affects as many boys as girls, but twice as many girls during adolescence.2 Suicide is associated with chronic mood disorders such as depression or psychosis and those afflicted are 10 to 20 times more likely to commit suicide. The risk of suicide is especially high in people with untreated bipolar disorder (manic-depression).3 The percentage of high school students who in 2017 reported that they had thought seriously about committing suicide in the last year was 17%.4 The proportion of students who reported having attempted suicide was 7% in 2017. A smaller proportion, 2.4% of high school students, reported requiring medical attention as a result of a suicide attempt in 2017. Teen suicide rates have reached 11.8 per 100,000 in 2017—a record high. In 2017, suicide was the second leading cause of death among individuals between the ages of 10 and 34. In 2017, rates of suicide among male teens were highest among American Indians (28.8 per 100,000) and non-Hispanic whites (22.0 per 100,000), followed by Hispanics (12.5), Asian or Pacific Islanders (11.6), and blacks (11.1). Among females, American Indian teens had the highest rate at 10.2 per 100,000, followed by non-Hispanic white teens at 5.8, and Asian or Pacific Islander teens at 5.2.5 Data in the figure below is from the U.S. National Institute of Mental Health.6 Personal

Family

Environmental

Prevention A healthy lifestyle can help Prevention of anxiety and depression Why some children develop anxiety, or depression, or suicidal tendencies is not well understood. Factors that cannot be changed, including biology and temperament, probably play a role. However, children are more likely to develop anxiety or depression when they experience trauma or stress, when they are maltreated, when they are bullied or rejected by other children, or when their own parents have anxiety or depression. In addition to getting the right treatment, leading a healthy lifestyle can help prevent or manage depression or anxiety. Healthy behaviors include:

Comprehensive community-based prevention Modest success has been accomplished through the Garrett Lee Smith Suicide Prevention Program (GLS) that focuses on training gatekeepers how to identify children and youth at risk by attention to the warning signs of suicide and referring at risk youth to appropriate support.8 Gatekeepers include those who have regular contact with large numbers of youths on a regular basis such as teachers, public school staff, peer educators and physicians. Limiting access to firearms An important risk factor for suicide in the United States is access to firearms. Among those of all ages who committed suicide in 2013, guns were used in 51% of completed suicides.9 Self-injury with a gun is fatal 84% of the time. This contrasts with an average of only 4% success by all other means. Suicide by suffocation/hanging is 69% fatal, and falls are 31% fatal, but together they account for fewer than half the number of deaths that guns claim each year. There is strong evidence that access to firearms in the home is associated with a significantly increased suicide risk and that reducing gun access for people at risk will reduce suicide. Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and antidepressant medication The principal options for treating depression and bipolar disorder are anti-depressant medications and psychotherapy including cognitive behavioral therapy, an effective evidence-based intervention for the prevention of suicide.10 Antidepressant medication is effective in treating depression among youth. One of the largest studies of antidepressant use in youth showed that patients treated with CBT and fluoxetine or fluoxetine had significantly greater improvements in depressive symptoms compared with patients treated with CBT alone or those who received a placebo.11 Other promising preventive approaches include community level awareness and education activities, strengthened mental health care and addiction treatment because opioid use is associated with increased risk of suicide as well as accidental overdose deaths.12 13 Social and economic factors associated with increased risk of suicide Most attention to the prevention of suicide has been focused on counseling, education and clinical interventions at the individual level. It has been pointed out that prevention of adversities associated with vulnerability to distress and disease and the strengthening of community support have the potential to decrease the incidence of suicide.14 The following factors at the levels of society, community relationships and individuals are likely to be relevant to risk of suicide. Societal

Community

Relationship

Individual

Asking for help Depression should not be neglected. Do not hesitate to seek the assistance of your pediatrician or a child and adolescent psychiatrist. A critical decision is whether a child is at acute risk of harm and if hospitalization is necessary to ensure safety to self and others.15 These factors, in turn, can be influenced by the severity of depression, presence of suicidal and/or homicidal symptoms, psychosis, substance dependence, agitation, adherence to treatment, parental psychopathology and family functioning. Family dynamics—which may include discord, lack of support and a controlling or authoritarian relationship—should also be evaluated to assist in diagnosis and treatment.20 If your child has suicidal thoughts, there is a new national crisis hotline number: 988. This 3-digit number will connect callers to the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline (accessed directly at 800-273-TALK or 800-273-8255) and route them to a local crisis center, staffed by trained crisis workers. The service is free, confidential, and available 24 hours a day, seven days a week. This hotline can also be used by anyone who would like to talk about life stresses or an emotional issue. Endnotes 1 Zimmerman M. Using the 9-Item Patient Health Questionnaire to Screen for and Monitor Depression. JAMA. 2019;322(21):2125–2126. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2019.15883 2 Birmaher B, Brent D; AACAP Work Group on Quality Issues, et al. Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with depressive disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007;46(11):1503-26. 3 Parikh SG, Depression and Anxiety, Scientific American White Paper, 2015. p. 15-16 4 Child Trends Databank. (2019). Suicidal teens. Available at: https://www.childtrends.org/?indicators=suicidal-teens 5 Child Trends. (2019). Teen Homicide, Suicide and Firearm Deaths. Retrieved from https://www.childtrends.org/indicators/teen-homicide-suicide-and-firearm-deaths. 6 Suicide. National Institute for Mental Health. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/suicide.shtml 7 Depression in Children and Youth. Canadian Pediatric Society. https://www.kidsnewtocanada.ca/mental-health/depression 8 Walrath C, Garraza LG, Reid H, et al. Impact of Garrett Lee Smith Suicide Prevention Program on Suicide Mortality. Am J. Public Health. 2015;105(5):986-993. 9 Swanson JW, Bonnie RJ, Appelbaum PS. Getting Serious About Reducing Suicide: More “How” and Less “Why”. JAMA. 2015;314(21):2229–2230. doi:10.1001/jama.2015.15566 10 Brown GK, Ten Have T, Henriques GR, Xie SX, Hollander JE, Beck AT. Cognitive therapy for the prevention of suicide attempts: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2005;294:563-570 11 March JS, Silva S, Petrycki S, et al. The Treatment for Adolescents with Depression Study (TADS): Long-term effectiveness and safety outcomes. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2007;64(10):1132-43. 12 Bohnert ASB, Ilgen MA. Understanding Links among Opioid Use, Overdose, and Suicide. N Engl J Med. 2019; 380:71-79. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMra1802148 13 Fazel S, Runeson B. Suicide. N Engl J Med. 2020; 382(3):266-274. 14 Caine ED. Forging and agenda for suicide prevention in the United States. Am J. Public Health. 2013;103(5):822-829. 15 American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with suicidal behavior. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2001;40(7 Suppl):24S-51S.

|

Depression in Children and Youth. Canadian Pediatric Society.

|

|||